Understanding Futures Contracts

Margins and Leverage Basics

Futures trading has its own structure and rules.

Some concepts overlap with stocks or options, but futures are a distinct instrument with mechanics that matter. Margin, leverage, contract specifications, and trading hours are not secondary details. They define how risk behaves and how positions actually function.

This post focuses on those mechanics.

Futures contracts are standardized instruments

Every futures contract is standardized and defined by an exchange. In the U.S., most contracts retail traders interact with are listed on the CME Group.

This includes equity index futures, interest rates, metals, energy, and agricultural products.

Each contract has a dedicated specification page that defines the rules of engagement.

Key fields you will see on every contract specification page include:

Contract size

Tick size and tick value

Trading hours

Initial and maintenance margin

Settlement type and expiration

Price limits and other constraints

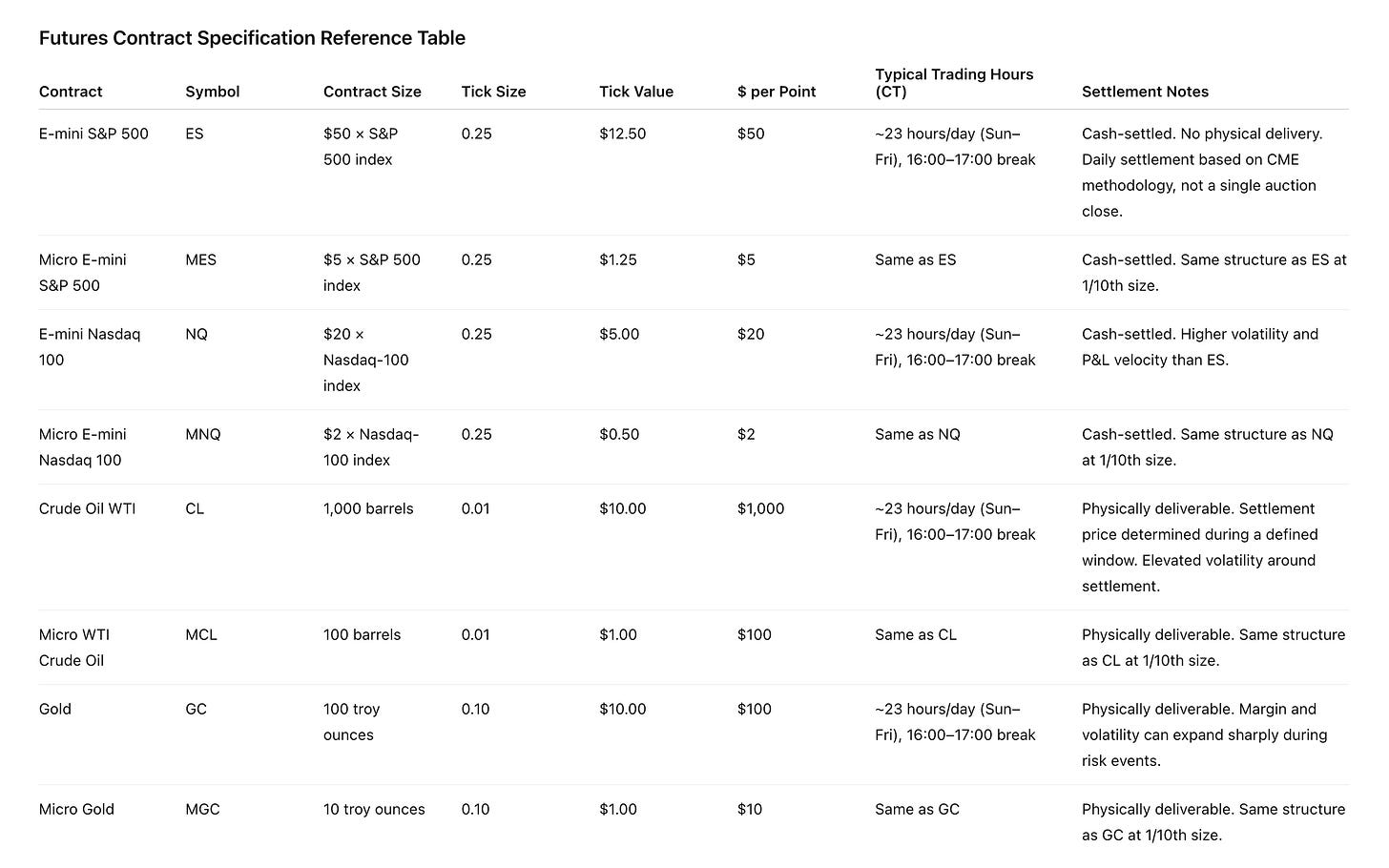

For example, here’s the contract specification page for the E-mini S&P 500 (ES).

How to read a futures contract specification page

At first glance, these pages can feel dense, this is normal.

The good news is that as a day trader, you only need to understand a handful of fields to be operationally competent.

The most important ones:

Contract size

Contract size tells you what one contract represents.

In the case of ES, one contract represents exposure to the S&P 500 index at $50 per index point. If ES is trading at 5,000, one contract represents $250,000 of notional exposure.

You do not choose this. The exchange defines it.

This is the foundation that everything else builds on.

Tick size

Tick size is the smallest price movement the contract can make.

Markets do not move in arbitrary decimals. They move in fixed increments defined by the contract.

For ES, the minimum price fluctuation is 0.25 index points.

Tick value

Tick value tells you how much money you make or lose per tick, per contract.

This is where many traders underestimate risk. A small-looking price move can represent a meaningful P&L change.

For ES:

Tick size: 0.25 points

Tick value: $12.50 per contract

That means:

A 1-point move equals 4 ticks

A 1-point move equals $50 per contract

If you trade 2 contracts, that is $100 per point.

If you trade 5 contracts, that is $250 per point.

This has nothing to do with margin.

Margin determines whether you can hold the position.

Tick value determines how fast your P&L moves.

Trading hours

Not all futures trade the same session.

Some contracts trade nearly 23 hours per day with short maintenance breaks. Others have more defined settlement windows that materially affect liquidity and volatility.

If you hold positions without knowing when a market settles or pauses, you are taking risks you may not be aware of.

What leverage actually means in futures

In futures, leverage is not something you choose. It is a byproduct of margin.

When you trade a futures contract, you control a large notional position while posting a relatively small amount of capital as margin. That margin is not a down payment and it is not a cap on losses. It is a performance bond that must be maintained as prices move.

As the market moves against you, losses are debited in real time. If account equity falls below maintenance margin, the position must be reduced, closed, or supported with additional capital.

This is where leverage becomes tangible.

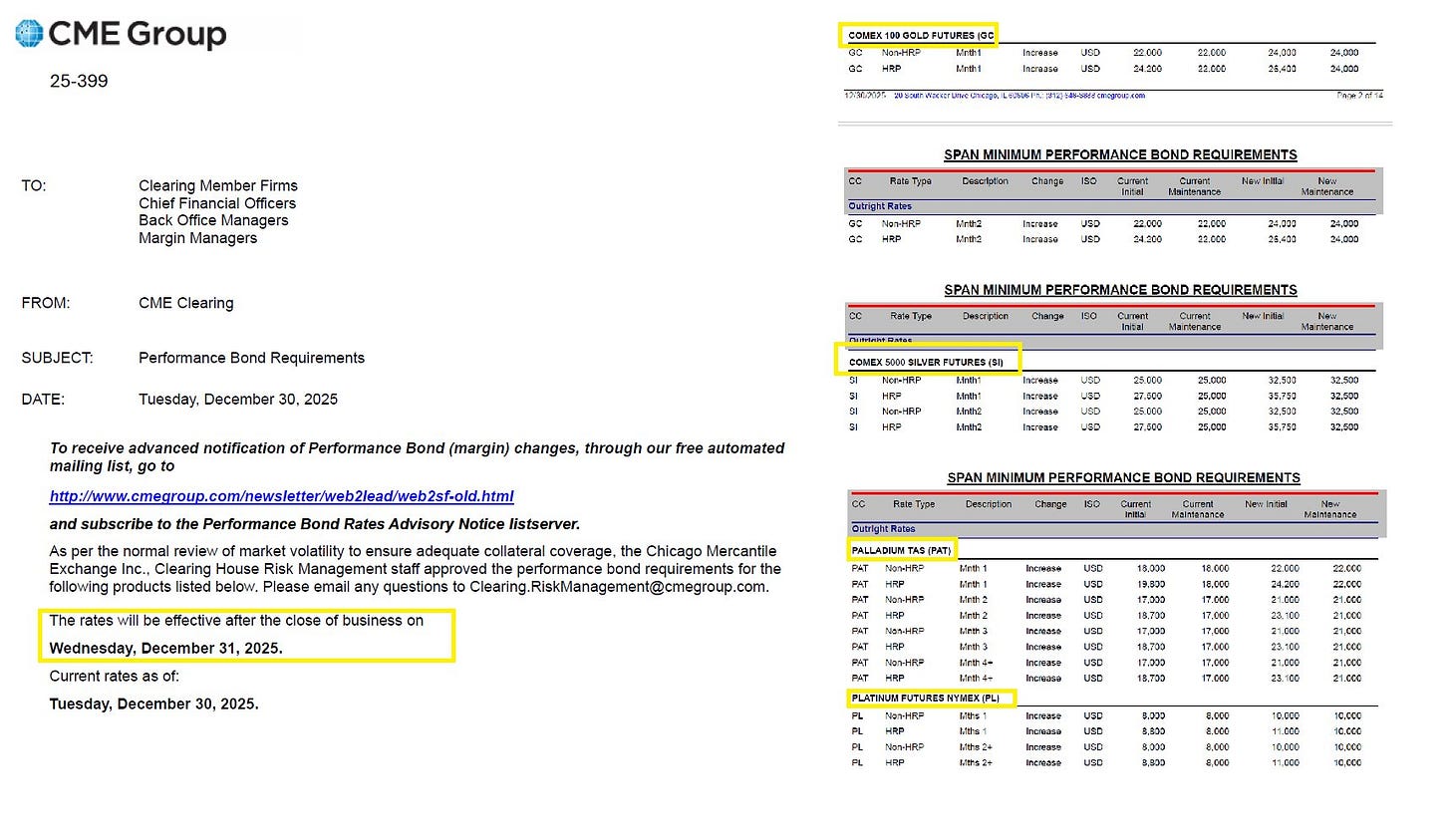

Margin requirements are set by the exchange and can change. When margins increase, effective leverage decreases instantly, regardless of your intent or positioning.

A recent example is CME Group raising margin requirements on Silver futures during a period of heightened volatility. Traders who were comfortably margined the day before suddenly needed significantly more capital to hold the same position. Many were forced to reduce or exit positions, not because their thesis changed, but because the rules changed underneath them.

In futures, leverage is dynamic. It is shaped by volatility, exchange policy, and margin requirements, not just by how many contracts you choose to trade.

Tick size and P&L velocity

Every futures contract moves in ticks. Each tick has a fixed dollar value.

This is what gives futures their precision and their danger.

Before placing a trade, you should be able to answer one question immediately:

“How much money do I make or lose if this moves one point against me?”

If you cannot answer that, you are trading blind.

Below I’ve created a reference table for specs on different futures contracts:

Not all futures trade the same hours

Futures contracts do not share the same closing or settlement behavior. Those differences matter when positions are held beyond the most liquid parts of the session.

Consider E-mini S&P 500 and Crude Oil WTI.

ES trades nearly 23 hours per day with a short maintenance break. There is no single cash-style close, and settlement is based on a defined calculation rather than a fixed auction.

CL also trades most of the day, but its settlement price is determined during a specific window. Liquidity and volatility often shift noticeably around that settlement time.

Holding positions across these periods carries different risks depending on the contract. Knowing when a market settles is part of knowing what risk you are actually holding.

Beginners should trade smaller than they think

When I first started, micro futures were not available, but boy I wish I would’ve had them!

Many new futures traders make is trading contracts that are too large for their account size and experience level.

Just because you can trade ES does not mean you should.

Micro contracts exist for a reason. They allow you to learn execution, mechanics, and emotional responses without oversized risk.

Futures reward precision. They punish sloppiness.

There is no downside to trading smaller while you build competence. There is real damage in trading too big, too early.

This is a long-term skill, not a shortcut.

Closing thoughts

This post is the foundation.

In future posts, we will build on this by layering execution, session structure, order flow, and context on top of these mechanics.

But none of that works if the basics are not solid.

This is where consistency actually starts.

P.S. If you use the Substack app, you can have it read the articles out loud to you.